How Did The Development Of Coined Money Change Trade?

The history of money concerns the evolution throughout fourth dimension of systems that provide the functions of money. Such systems can exist understood every bit means of trading wealth indirectly; not direct equally with bartering. Money is a mechanism that facilitates this procedure.

Money may have a concrete class as in coins and notes, or may exist every bit a written or electronic account. It may have intrinsic value (article money), be legally exchangeable for something with intrinsic value (representative money), or only have nominal value (fiat coin).[i]

Overview [edit]

The invention of money took place earlier the outset of written history.[two] [iii] Consequently, whatever story of how money get-go developed is by and large based on conjecture and logical inference.

The pregnant evidence establishes many things were traded in ancient markets that could exist described as a medium of exchange. These included livestock and grain–things straight useful in themselves – but also merely attractive items such as cowrie shells or beads[ citation needed ] were exchanged for more useful commodities. However, such exchanges would exist better described as barter, and the mutual bartering of a item article (especially when the commodity items are not fungible) does not technically make that commodity "money" or a "commodity money" like the shekel – which was both a coin representing a specific weight of barley, and the weight of that sack of barley.[4]

Due to the complexities of aboriginal history (aboriginal civilizations developing at different paces and not keeping accurate records or having their records destroyed), and considering the aboriginal origins of economic systems precede written history, information technology is impossible to trace the true origin of the invention of money. Further, evidence in the histories[5] supports the idea that money has taken two primary forms divided into the wide categories of coin of business relationship (debits and credits on ledgers) and money of substitution (tangible media of commutation made from dirt, leather, paper, bamboo, metal, etc.).

As "money of account" depends on the power to record a count, the tally stick was a significant development. The oldest of these dates from the Aurignacian, virtually thirty,000 years ago.[six] [vii] The 20,000-year-old Ishango Bone – found virtually one of the sources of the Nile in the Autonomous Republic of Congo – seems to use matched tally marks on the thigh bone of a baboon for correspondence counting. Accounting records – in the monetary system sense of the term bookkeeping – dating back more than vii,000 years have been establish in Mesopotamia,[8] and documents from ancient Mesopotamia show lists of expenditures, and goods received and traded and the history of accounting evidences that coin of account pre-dates the use of coinage by several thou years. David Graeber proposes that coin every bit a unit of measurement of account was invented when the unquantifiable obligation "I owe you one" transformed into the quantifiable notion of "I owe you i unit of something". In this view, money emerged first every bit money of business relationship and only later took the grade of money of exchange.[9] [10]

Regarding money of commutation, the use of representative money historically pre-dates the invention of coinage as well.[ii] In the aboriginal empires of Egypt, Babylon, India and People's republic of china, the temples and palaces frequently had commodity warehouses which made apply of dirt tokens[2] and other materials which served every bit evidence of a merits upon a portion of the goods stored in the warehouses.[11] Considering these tokens could exist redeemed at the warehouse for the commodity they represented, they were able to be traded in the markets as if they were the commodity or given to workers as payment.

While not the oldest form of coin of substitution, various metals (both common and precious metals) were also used in both barter systems and monetary systems and the historical apply of metals provides some of the clearest analogy of how the castling systems gave birth to monetary systems. The Romans' employ of bronze, while not among the more aboriginal examples, is well-documented, and it illustrates this transition clearly. First, the "aes rude" (rough bronze) was used. This was a heavy weight of unmeasured bronze used in what was probably a barter arrangement—the barter-ability of the bronze was related exclusively to its usefulness in metalsmithing and it was bartered with the intent of being turned into tools. The next historical step was bronze in bars that had a v-pound pre-measured weight (presumably to make barter easier and more than fair), called "aes signatum" (signed statuary), which is where debate arises between if this is notwithstanding the castling organisation or at present a budgetary system. Finally, there is a clear break from the use of bronze in barter into its undebatable employ as coin considering of lighter measures of bronze not intended to be used as annihilation other than coinage for transactions. The aes grave (heavy bronze) (or As) is the starting time of the utilize of coins in Rome, just not the oldest known instance of metal coinage.

Gold and silvery have been the most mutual forms of coin throughout history. In many languages, such as Castilian, French, Hebrew and Italian, the word for silver is notwithstanding directly related to the give-and-take for coin. Sometimes other metals were used. For instance, Ancient Sparta minted coins from iron to discourage its citizens from engaging in foreign trade.[12] In the early 17th century Sweden lacked precious metals, so produced "plate money": large slabs of copper 50 cm or more in length and width, stamped with indications of their value.

Gilded coins began to be minted once again in Europe in the 13th century. Frederick II is credited with having reintroduced golden coins during the Crusades. During the 14th century Europe changed from use of argent in currency to minting of golden.[xiii] [14] Vienna made this change in 1328.[13]

Metal-based coins had the advantage of carrying their value within the coins themselves – on the other manus, they induced manipulations, such every bit the clipping of coins to remove some of the precious metal. A greater problem was the simultaneous co-existence of gilded, silverish and copper coins in Europe. The exchange rates between the metals varied with supply and demand. For instance the aureate republic of guinea money began to rising against the silver crown in England in the 1670s and 1680s. Consequently, argent was exported from England in commutation for gold imports. The effect was worsened with Asian traders not sharing the European appreciation of gilt altogether — golden left Asia and silver left Europe in quantities European observers like Isaac Newton, Chief of the Royal Mint observed with unease.[15]

Stability came when national banks guaranteed to change silver money into gold at a fixed rate; it did, still, not come up easily. The Depository financial institution of England risked a national financial catastrophe in the 1730s when customers demanded their money be changed into gold in a moment of crisis. Eventually London's merchants saved the banking company and the nation with fiscal guarantees.[ commendation needed ]

Another step in the evolution of money was the change from a money being a unit of measurement of weight to being a unit of value. A stardom could be made between its commodity value and its specie value. The departure in these values is seigniorage.[sixteen] [ commendation needed ]

Theories of money [edit]

The primeval ideas included Aristotle's "metallist" and Plato's "chartalist" concepts, which Joseph Schumpeter integrated into his own theory of money as forms of classification.[17] Especially, the Austrian economist attempted to develop a catallactic theory of money out of Merits Theory.[18] Schumpeter'south theory had several themes simply the near important of these involve the notions that money can be analyzed from the viewpoint of social bookkeeping and that information technology is as well firmly connected to the theory of value and price.[xix]

In that location are at to the lowest degree two theories of what coin is, and these tin can influence the interpretation of historical and archeological show of early on monetary systems. The commodity theory of money (money of commutation) is preferred past those who wish to view money as a natural outgrowth of market activity.[20] Others view the credit theory of money (coin of business relationship) every bit more plausible and may posit a central office for the state in establishing money. The Commodity theory is more widely held and much of this article is written from that point of view.[21] Overall, the dissimilar theories of money developed by economists largely focus on functions, utilize, and direction of money.[17]

Other theorists too note that the status of a particular form of coin always depends on the status ascribed to it by humans and past club.[22] For case, gold may be seen as valuable in one social club but not in another or that a banking concern note is merely a piece of paper until information technology is agreed that it has monetary value.[22]

Money supply [edit]

In modern times economists accept sought to classify the different types of money supply. The different measures of the money supply take been classified by various central banks, using the prefix "M". The supply classifications oftentimes depend on how narrowly a supply is specified, for example the "M"due south may range from M0 (narrowest) to M3 (broadest). The classifications depend on the particular policy conception used:

- M0 : In some countries, such as the Uk, M0 includes bank reserves, so M0 is referred to as the budgetary base, or narrow money.[23]

- MB: is referred to as the monetary base or total currency. This is the base of operations from which other forms of money (like checking deposits, listed below) are created and is traditionally the most liquid measure of the coin supply.[24]

- M1: Banking company reserves are not included in M1.

- M2: Represents M1 and "close substitutes" for M1.[25] M2 is a broader classification of money than M1. M2 is a key economic indicator used to forecast inflation.[26]

- M3: M2 plus large and long-term deposits. Since 2006, M3 is no longer published by the U.S. fundamental bank.[27] All the same, there are still estimates produced past diverse private institutions.

- MZM: Money with naught maturity. Information technology measures the supply of financial assets redeemable at par on demand. Velocity of MZM is historically a relatively accurate predictor of aggrandizement.[28] [29] [xxx]

Technologies [edit]

Assaying [edit]

Assaying is analysis of the chemical composition of metals. The discovery of the touchstone[ when? ] for assaying helped the popularisation of metal-based commodity money and coinage.[ citation needed ] Any soft metal, such every bit aureate, tin be tested for purity on a touchstone. As a outcome, the use of gilt for as commodity money spread from Asia Minor, where it first gained wide usage.[ dubious ]

A touchstone allows the amount of gold in a sample of an alloy to been estimated. In turn this allows the blend'south purity to be estimated. This allows coins with a uniform amount of gold to exist created. Coins were typically minted by governments and then stamped with an keepsake that guaranteed the weight and value of the metal. However, besides equally intrinsic value coins had a face up value. Sometimes governments would reduce the corporeality of precious metal in a money (reducing the intrinsic value) and affirm the same face value, this practice is known equally debasement.[ citation needed ]

Prehistory: predecessors of money and its emergence [edit]

Non-budgetary exchange [edit]

Gifting and debt [edit]

There is no show, historical or contemporary, of a society in which barter is the main way of exchange;[31] instead, non-monetary societies operated largely forth the principles of gift economy and debt.[32] [33] [34] When barter did in fact occur, information technology was usually between either complete strangers or potential enemies.[35]

Barter [edit]

With barter, an individual possessing whatsoever surplus of value, such as a measure of grain or a quantity of livestock, could directly substitution information technology for something perceived to have similar or greater value or utility, such as a clay pot or a tool, still, the capacity to acquit out barter transactions is limited in that it depends on a coincidence of wants. For example, a farmer has to find someone who not only wants the grain he produced but who could also offer something in return that the farmer wants.

Hypothesis of castling as the origin of money [edit]

In Politics Book ane:ix[36] (c. 350 BC) the Greek philosopher Aristotle contemplated the nature of money. He considered that every object has 2 uses: the original purpose for which the object was designed, and every bit an item to sell or barter.[37] The assignment of monetary value to an otherwise insignificant object such as a money or promissory note arises as people acquired a psychological capacity to place trust in each other and in external authority within barter exchange.[38] [39] Finding people to barter with is a time-consuming procedure; Austrian economist Carl Menger hypothesised that this reason was a driving force in the cosmos of monetary systems – people seeking a way to stop wasting their time looking for someone to castling with.[40]

In his book Debt: The Start 5,000 Years, anthropologist David Graeber argues against the proposition that coin was invented to replace barter.[41] The problem with this version of history, he suggests, is the lack of any supporting testify. His research indicates that gift economies were mutual, at to the lowest degree at the beginnings of the starting time agrarian societies, when humans used elaborate credit systems. Graeber proposes that money as a unit of account was invented the moment when the unquantifiable obligation "I owe yous one" transformed into the quantifiable notion of "I owe you one unit of something". In this view, money emerged first equally credit and merely afterwards acquired the functions of a medium of exchange and a store of value.[nine] [10] Graeber'due south criticism partly relies on and follows that fabricated by A. Mitchell Innes in his 1913 article "What is money?". Innes refutes the barter theory of money, by examining historic bear witness and showing that early coins never were of consistent value nor of more or less consequent metal content. Therefore, he concludes that sales is non exchange of goods for some universal commodity, only an exchange for credit. He argues that "credit and credit alone is coin".[42] Anthropologist Caroline Humphrey examines the available ethnographic data and concludes that "No example of a barter economy, pure and unproblematic, has ever been described, let lone the emergence from it of money; all available ethnography suggests that there never has been such a matter".[31]

Economists Robert P. Potato and George Selgin replied to Graeber maxim that the castling hypothesis is consistent with economic principles, and a barter organization would be too brief to exit a permanent record.[43] [44] John Alexander Smith from Bella Caledonia said that in this exchange Graeber is the i acting equally a scientist by trying to falsify the barter hypotheses, while Selgin is taking a theological stance past taking the hypothesis equally truth revealed from authority.[45]

Gift economy [edit]

In a gift economy, valuable goods and services are regularly given without whatsoever explicit agreement for immediate or future rewards (i.e. there is no formal quid pro quo).[46] Ideally, simultaneous or recurring giving serves to broadcast and redistribute valuables within the community.

At that place are diverse social theories concerning gift economies. Some consider the gifts to be a course of reciprocal altruism, where relationships are created through this type of exchange.[47] Another interpretation is that implicit "I owe you" debt[48] and social status are awarded in return for the "gifts".[49] Consider for example, the sharing of food in some hunter-gatherer societies, where food-sharing is a safeguard against the failure of any individual's daily foraging. This custom may reflect altruism, information technology may be a form of informal insurance, or may bring with it social condition or other benefits.

Emergence of money [edit]

Anthropologists have noted many cases of 'primitive' societies using what looks to us very like money but for non-commercial purposes, indeed commercial employ may have been prohibited:

Ofttimes, such currencies are never used to buy and sell anything at all. Instead, they are used to create, maintain, and otherwise reorganize relations between people: to arrange marriages, establish the paternity of children, caput off feuds, panel mourners at funerals, seek forgiveness in the case of crimes, negotiate treaties, acquire followers—almost anything but merchandise in yams, shovels, pigs, or jewelry.[50]

This suggests that the basic thought of coin may have long preceded its awarding to commercial trade.

After the domestication of cattle and the start of cultivation of crops in 9000–6000 BC, livestock and plant products were used as money.[51] However, it is in the nature of farm production that things take time to achieve fruition. The farmer may need to buy things that he cannot pay for immediately. Thus the idea of debt and credit was introduced, and a need to record and track information technology arose.

The establishment of the showtime cities in Mesopotamia (c. 3000 BCE) provided the infrastructure for the next simplest form of coin of account—asset-backed credit or Representative money. Farmers would deposit their grain in the temple which recorded the eolith on clay tablets and gave the farmer a receipt in the class of a clay token which they could and so use to pay fees or other debts to the temple.[ii] Since the bulk of the deposits in the temple were of the primary staple, barley, a stock-still quantity of barley came to be used equally a unit of measurement of account.[52]

Aristotle's opinion of the creation of money of exchange as a new thing in society is:

When the inhabitants of one land became more than dependent on those of another, and they imported what they needed, and exported what they had likewise much of, money necessarily came into use.[53]

Trading with foreigners required a course of money which was non tied to the local temple or economy, money that carried its value with information technology. A tertiary, proxy, commodity that would mediate exchanges which could not be settled with directly barter was the solution. Which commodity would be used was a affair of agreement betwixt the two parties, but as trade links expanded and the number of parties involved increased the number of acceptable proxies would accept decreased. Ultimately, i or two commodities were converged on in each trading zone, the near mutual beingness gilded and silverish.

This procedure was contained of the local monetary system so in some cases societies may take used money of substitution before developing a local money of account. In societies where foreign merchandise was rare coin of substitution may have appeared much afterwards than money of account.

In early Mesopotamia copper was used in trade for a while merely was presently superseded by silver. The temple (which financed and controlled about strange trade) stock-still exchange rates between barley and silver, and other important commodities, which enabled payment using whatever of them. Information technology also enabled the all-encompassing use of accounting in managing the whole economy, which led to the development of writing and thus the beginning of history.[54]

Bronze Age: commodity money, credit and debt [edit]

Many cultures around the globe developed the use of commodity money, that is, objects that have value in themselves likewise every bit value in their use every bit money.[55] Ancient China, Africa, and India used cowry shells.

The Mesopotamian civilization developed a big-scale economy based on article money. The shekel was the unit of weight and currency, offset recorded c. 3000 BC,[ dubious ] which was nominally equivalent to a specific weight of barley that was the preexisting and parallel form of currency.[4] [56] The Babylonians and their neighboring city states later developed the earliest system of economics as we retrieve of it today, in terms of rules on debt,[48] legal contracts and law codes relating to business concern practices and private property. Money emerged when the increasing complexity of transactions made information technology useful.[57] [58]

The Code of Hammurabi, the best-preserved aboriginal police force lawmaking, was created c. 1760 BC (middle chronology) in ancient Babylon. It was enacted by the sixth Babylonian king, Hammurabi. Before collections of laws include the lawmaking of Ur-Nammu, king of Ur (c. 2050 BC), the Code of Eshnunna (c. 1930 BC) and the code of Lipit-Ishtar of Isin (c. 1870 BC).[5] These law codes formalized the role of coin in civil club. They set amounts of involvement on debt, fines for "wrongdoing", and bounty in money for various infractions of formalized law.

It has long been causeless that metals, where available, were favored for use as proto-money over such commodities as cattle, cowry shells, or salt, because metals are at once durable, portable, and easily divisible.[59] The use of gilt as proto-money has been traced back to the 4th millennium BC when the Egyptians used gold bars of a set weight as a medium of exchange,[ citation needed ] equally had been washed before in Mesopotamia with silverish bars.[ citation needed ]

The first mention in the Bible of the use of money is in the Book of Genesis[60] in reference to criteria for the circumcision of a bought slave. Later, the Cavern of Machpelah is purchased (with silver[61] [62]) by Abraham, some time subsequently 1985 BC, although scholars believe the book was edited in the 6th or fifth centuries BC.[63] [64] [65] [66]

g BC – 400 Advertizing [edit]

First coins [edit]

Greek drachm of Aegina. Obverse: Land turtle. Reverse: ΑΙΓ(INA) and dolphin

A 7th century i-third stater coin from Lydia, shown larger

From about m BC, money in the form of small-scale knives and spades made of bronze was in apply in China during the Zhou dynasty, with cast bronze replicas of cowrie shells in apply before this. The first manufactured actual coins seem to have appeared separately in Bharat, Communist china, and the cities effectually the Aegean Sea 7th century BC.[67] While these Aegean coins were stamped (heated and hammered with insignia), the Indian coins (from the Ganges river valley) were punched metal disks, and Chinese coins (outset developed in the Great Obviously) were cast bronze with holes in the heart to exist strung together. The dissimilar forms and metallurgical processes imply a separate development.

All modern coins, in plow, are descended from the coins that appear to take been invented in the kingdom of Lydia in Asia Minor somewhere effectually 7th century BC and that spread throughout Hellenic republic in the following centuries: disk-shaped, made of gold, silvery, statuary or imitations thereof, with both sides begetting an prototype produced by stamping; one side is often a human head.[68]

Maybe the first ruler in the Mediterranean known to have officially set standards of weight and coin was Pheidon.[69] Minting occurred in the late seventh century BC amidst the Greek cities of Asia Minor, spreading to the Greek islands of the Aegean and to the south of Italia by 500 BC.[70] The first stamped money (having the mark of some authorization in the form of a picture or words) tin can exist seen in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. Information technology is an electrum stater, coined at Aegina island. This coin[71] dates to nearly seventh century BC.[72]

Herodotus dated the introduction of coins to Italia to the Etruscans of Populonia in well-nigh 550 BC.[73]

Other coins made of electrum (a naturally occurring alloy of silver and gold) were manufactured on a larger calibration nearly 7th century BC in Lydia (on the declension of what is now Turkey).[74] Similar coinage was adopted and manufactured to their ain standards in nearby cities of Ionia, including Mytilene and Phokaia (using coins of electrum) and Aegina (using silver) during the seventh century BC, and soon became adopted in mainland Greece, and the Persian Empire (afterward it incorporated Lydia in 547 BC).

The use and export of silver coinage, forth with soldiers paid in coins, contributed to the Athenian Empire'southward authorization of the region in the 5th century BC. The argent used was mined in southern Attica at Laurium and Thorikos by a huge workforce of slave labour. A major silver vein discovery at Laurium in 483 BC led to the huge expansion of the Athenian armed services armada.

The worship of Moneta is recorded past Livy with the temple built in the fourth dimension of Rome 413 (123)[ description needed ]; a temple consecrated to the same goddess was congenital in the earlier part of the 4th century (perhaps the same temple).[75] [76] [77] For four centuries the temple independent the mint of Rome.[78] [seventy] The name of the goddess thus became the source of numerous words in English and the Romance languages, including the words "money" and "mint"

Roman banking arrangement [edit]

| | This section needs expansion. Yous can aid by calculation to it. (Baronial 2017) |

400–1450 [edit]

Medieval coins and moneys of account [edit]

Charlemagne, in 800 Advertizing, implemented a series of reforms upon condign "Holy Roman Emperor", including the issuance of a standard coin, the silver penny. Between 794 and 1200 the penny was the only denomination of coin in Western Europe. Minted without oversight by bishops, cities, feudal lords and fiefdoms, by 1160, coins in Venice independent only 0.05g of silver, while England's coins were minted at 1.3g. Large coins were introduced in the mid-13th century. In England, a dozen pennies was chosen a "shilling" and twenty shillings a "pound".[79]

Debasement of coin was widespread. Significant periods of debasement took place in 1340-lx and 1417-29, when no modest coins were minted, and by the 15th century the issuance of minor coin was further restricted past government restrictions and even prohibitions. With the exception of the Great Debasement, England'southward coins were consistently minted from sterling silverish (silver content of 92.5%). A lower quality of silverish with more copper mixed in, used in Barcelona, was called "billion".[79]

First paper coin [edit]

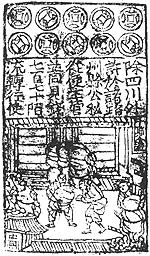

Earliest banknote from China during the Vocal Dynasty which is known every bit "Jiaozi"

Paper money was introduced in Song dynasty Mainland china during the 11th century.[80] The development of the banknote began in the seventh century, with local bug of paper currency. Its roots were in merchant receipts of deposit during the Tang dynasty (618–907), as merchants and wholesalers desired to avoid the heavy majority of copper coinage in big commercial transactions.[81] [82] [83] The issue of credit notes is often for a express duration, and at some discount to the promised corporeality later. The jiaozi nevertheless did not supplant coins during the Song Dynasty; paper money was used alongside the coins. The central government soon observed the economic advantages of press paper coin, issuing a monopoly right of several of the deposit shops to the issuance of these certificates of deposit.[84] By the early 12th century, the amount of banknotes issued in a single year amounted to an annual rate of 26 million strings of cash coins.[85]

The taka was widely used across Due south Asia during the sultanate period

Silver money of the Maurya Empire, known every bit rūpyarūpa, with symbols of wheel and elephant. 3rd century BC.

In the Indian subcontinent, Sher Shah Suri (1540–1545), introduced a argent coin chosen a rupiya, weighing 178 grams. Its use was continued by the Mughal Empire.[86] The history of the rupee traces dorsum to Ancient Bharat circa 3rd century BC. Aboriginal Bharat was 1 of the earliest issuers of coins in the earth,[87] along with the Lydian staters, several other Middle Eastern coinages and the Chinese wen. The term is from rūpya, a Sanskrit term for silverish coin,[88] from Sanskrit rūpa, cute form.[89]

The imperial taka was officially introduced by the monetary reforms of Muhammad bin Tughluq, the emperor of the Delhi Sultanate, in 1329. Information technology was modeled as representative money, a concept pioneered as paper money by the Mongols in Red china and Persia. The tanka was minted in copper and brass. Its value was exchanged with gold and silver reserves in the imperial treasury. The currency was introduced due to the shortage of metals.[90]

Both the Kabuli rupee and the Kandahari rupee were used every bit currency in Afghanistan prior to 1891, when they were standardized as the Afghan rupee. The Afghan rupee, which was subdivided into 60 paisas, was replaced by the Afghan afghani in 1925.

Until the middle of the 20th century, Tibet'due south official currency was also known equally the Tibetan rupee.[91]

In the 13th century, paper coin became known in Europe through the accounts of travelers, such as Marco Polo and William of Rubruck.[92] Marco Polo's account of paper money during the Yuan dynasty is the subject of a affiliate of his book, The Travels of Marco Polo, titled "How the Great Kaan Causeth the Bark of Trees, Made into Something Like Paper, to Laissez passer for Coin All Over his State."[93] In medieval Italian republic and Flemish region, considering of the insecurity and impracticality of transporting large sums of money over long distances, money traders started using promissory notes. In the kickoff these were personally registered, simply they before long became a written social club to pay the amount to whomever had it in their possession.[94] These notes can be seen equally a predecessor to regular banknotes.[95]

Trade bills of exchange [edit]

Bills of exchange became prevalent with the expansion of European trade toward the end of the Center Ages. A flourishing Italian wholesale trade in textile, woolen wearable, vino, tin and other commodities was heavily dependent on credit for its rapid expansion. Goods were supplied to a buyer against a bill of exchange, which constituted the buyer'south promise to make payment at some specified future date. Provided that the buyer was reputable or the bill was endorsed by a apparent guarantor, the seller could then present the bill to a merchant banker and redeem information technology in money at a discounted value earlier it actually became due. The main purpose of these bills nevertheless was, that traveling with cash was particularly dangerous at the time. A deposit could be made with a banker in ane town, in turn a nib of exchange was handed out, that could exist redeemed in some other town.

These bills could also be used equally a form of payment by the seller to make additional purchases from his own suppliers. Thus, the bills – an early on form of credit – became both a medium of substitution and a medium for storage of value. Similar the loans made by the Egyptian grain banks, this merchandise credit became a significant source for the creation of new money. In England, bills of substitution became an important form of credit and money during last quarter of the 18th century and the get-go quarter of the 19th century before banknotes, checks and cash credit lines were widely available.[96]

Islamic Golden Age [edit]

At effectually the same fourth dimension in the medieval Islamic world, a vigorous monetary economy was created during the seventh–12th centuries on the footing of the expanding levels of circulation of a stable high-value currency (the dinar). Innovations introduced by Muslim economists, traders and merchants include the earliest uses of credit,[97] cheques, promissory notes,[98] savings accounts, transactional accounts, loaning, trusts, commutation rates, the transfer of credit and debt,[99] and banking institutions for loans and deposits.[99]

Indian subcontinent [edit]

In the Indian subcontinent, Sher Shah Suri (1540–1545), introduced a silver coin chosen a rupiya, weighing 178 grams. Its use was continued by the Mughal rulers.[86] The history of the rupee traces back to Ancient Bharat circa 3rd century BC. Ancient Republic of india was i of the earliest issuers of coins in the globe,[87] along with the Lydian staters, several other Middle Eastern coinages and the Chinese wen. The term is from rūpya, a Sanskrit term for silverish coin,[88] from Sanskrit rūpa, beautiful form.[100]

The imperial taka was officially introduced past the monetary reforms of Muhammad bin Tughluq, the emperor of the Delhi Sultanate, in 1329. Information technology was modeled as representative money, a concept pioneered as paper money by the Mongols in China and Persia. The tanka was minted in copper and brass. Its value was exchanged with gold and silver reserves in the regal treasury. The currency was introduced due to the shortage of metals.[90]

Tallies [edit]

The acceptance of symbolic forms of money meant that a symbol could exist used to correspond something of value that was available in physical storage somewhere else in space, such every bit grain in the warehouse; or something of value that would be available afterwards, such equally a promissory annotation or bill of exchange, a document ordering someone to pay a certain sum of money to another on a specific engagement or when certain weather condition have been fulfilled.

In the 12th century, the English language monarchy introduced an early version of the bill of exchange in the form of a notched piece of wood known as a tally stick. Tallies originally came into use at a time when newspaper was rare and plush, simply their utilize persisted until the early 19th century, even after newspaper money had become prevalent. The notches denoted various amounts of taxes payable to the Crown. Initially tallies were simply a form of receipt to the taxpayer at the time of rendering his dues. Every bit the acquirement department became more efficient, they began issuing tallies to denote a promise of the tax assessee to make future revenue enhancement payments at specified times during the year. Each tally consisted of a matching pair – 1 stick was given to the assessee at the time of assessment representing the corporeality of taxes to be paid later, and the other held by the Treasury representing the corporeality of taxes to exist nerveless at a future date.

The Treasury discovered that these tallies could also exist used to create money. When the Crown had exhausted its current resources, it could employ the tally receipts representing future tax payments due to the Crown as a form of payment to its own creditors, who in plow could either collect the tax revenue directly from those assessed or apply the same tally to pay their own taxes to the government. The tallies could as well be sold to other parties in exchange for aureate or silver money at a discount reflecting the length of time remaining until the revenue enhancement was due for payment. Thus, the tallies became an accepted medium of substitution for some types of transactions and an accepted store of value. Like the girobanks before it, the Treasury soon realized that it could also effect tallies that were not backed by any specific assessment of taxes. By doing and then, the Treasury created new money that was backed past public trust and confidence in the monarchy rather than by specific revenue receipts.[101]

1450–1971 [edit]

Goldsmith bankers [edit]

Goldsmiths in England had been craftsmen, bullion merchants, money changers, and money lenders since the 16th century. But they were not the first to act equally fiscal intermediaries; in the early 17th century, the scriveners were the starting time to keep deposits for the express purpose of relending them.[102] Merchants and traders had amassed huge hoards of gold and entrusted their wealth to the Royal Mint for storage. In 1640 King Charles I seized the individual golden stored in the mint as a forced loan (which was to be paid back over fourth dimension). Thereafter merchants preferred to store their gold with the goldsmiths of London, who possessed individual vaults, and charged a fee for that service. In exchange for each eolith of precious metal, the goldsmiths issued receipts certifying the quantity and purity of the metal they held as a bailee (i.eastward., in trust). These receipts could not be assigned (simply the original depositor could collect the stored goods). Gradually the goldsmiths took over the part of the scriveners of relending on behalf of a depositor and also adult mod banking practices; promissory notes were issued for coin deposited which by custom and/or law was a loan to the goldsmith,[103] i.due east., the depositor expressly allowed the goldsmith to use the money for whatever purpose including advances to his customers. The goldsmith charged no fee, or even paid interest on these deposits. Since the promissory notes were payable on demand, and the advances (loans) to the goldsmith's customers were repayable over a longer time menstruation, this was an early form of partial reserve cyberbanking. The promissory notes adult into an assignable musical instrument, which could broadcast as a safe and convenient form of money backed by the goldsmith'due south promise to pay.[104] Hence goldsmiths could advance loans in the class of gold money, or in the grade of promissory notes, or in the form of checking accounts.[105] Gold deposits were relatively stable, oftentimes remaining with the goldsmith for years on stop, then there was little risk of default and so long as public trust in the goldsmith'south integrity and fiscal soundness was maintained. Thus, the goldsmiths of London became the forerunners of British banking and prominent creators of new money based on credit.

Kickoff European banknotes [edit]

The first European banknotes were issued past Stockholms Banco, a predecessor of Sweden's central bank Sveriges Riksbank, in 1661.[106] These replaced the copper-plates beingness used instead as a means of payment,[107] although in 1664 the bank ran out of coins to redeem notes and ceased operating in the aforementioned year.

Inspired past the success of the London goldsmiths, some of whom became the forerunners of cracking English banks, banks began issuing paper notes quite properly termed "banknotes", which circulated in the same manner that government-issued currency circulates today. In England this exercise continued up to 1694. Scottish banks continued issuing notes until 1850, and still exercise upshot banknotes backed by Banking company of England notes. In the The states, this practice continued through the 19th century; at 1 fourth dimension there were more than 5,000 different types of banknotes issued by various commercial banks in America. Only the notes issued by the largest, most creditworthy banks were widely accepted. The scrip of smaller, lesser-known institutions circulated locally. Farther from home it was only accustomed at a discounted rate, if at all. The proliferation of types of money went hand in paw with a multiplication in the number of financial institutions.

These banknotes were a form of representative money which could be converted into gilt or silvery by application at the banking concern. Since banks issued notes far in excess of the gold and silverish they kept on deposit, sudden loss of public confidence in a bank could precipitate mass redemption of banknotes and result in bankruptcy.

In India the primeval paper money was issued past Depository financial institution of Hindostan (1770– 1832), Full general Depository financial institution of Bengal and Bihar (1773–75), and Bengal Bank (1784–91).[108]

The utilize of banknotes issued past private commercial banks as legal tender has gradually been replaced by the issuance of bank notes authorized and controlled past national governments. The Bank of England was granted sole rights to effect banknotes in England later 1694. In the The states, the Federal Reserve Bank was granted similar rights later on its institution in 1913. Until recently, these government-authorized currencies were forms of representative money, since they were partially backed by gold or silverish and were theoretically convertible into gilded or silver.

1971–present [edit]

In 1971, U.s.a. President Richard Nixon appear that the The states dollar would not be direct convertible to Aureate anymore. This mensurate effectively destroyed the Bretton Woods system by removing i of its key components, in what came to be known equally the Nixon shock. Since and then, the United states of america dollar, and thus all national currencies, are Complimentary-floating currencies. Additionally, international, national and local money is now dominated by virtual credit rather than real bullion.[ix]

Payment cards [edit]

In the late 20th century, payment cards such as credit cards and debit cards became the dominant way of consumer payment in the Showtime World. The Bankamericard, launched in 1958, became the first 3rd-party credit menu to acquire widespread use and be accepted in shops and stores all over the United States, soon followed by the Mastercard and the American Express.[109] Since 1980, Credit Carte du jour companies are exempt from state usury laws, and and so can accuse any interest rate they encounter fit.[110] Outside America, other payment cards became more than popular that credit cards, such equally France's Carte Bleue.[111]

Digital currency [edit]

The development of computer technology in the second part of the twentieth century allowed coin to be represented digitally. By 1990, in the United States, all money transferred between its central bank and commercial banks was in electronic class. Past the 2000s almost money existed every bit digital currency in banks databases.[112] In 2012, by number of transaction, twenty to 58 percent of transactions were electronic (dependent on country).[113] The do good of digital currency is that it allows for easier, faster, and more flexible payments.[114]

Cryptocurrencies [edit]

In 2008, Bitcoin was proposed by an unknown author/s under the pseudonym of Satoshi Nakamoto. It was implemented the aforementioned year. Its use of cryptography allowed the currency to have a trustless, fungible and tamper resistant distributed ledger called a blockchain. It became the showtime widely used decentralized, peer-to-peer, cryptocurrency.[115] [116] Other comparable systems had been proposed since the 1980s.[117] The protocol proposed past Nakamoto solved what is known as the double-spending problem without the demand of a trusted third-party.

Since Bitcoin's inception, thousands of other cryptocurrencies have been introduced.

See also [edit]

- Axe-monies

- Primal bank

- Commissary notes

- Money creation

- Monetary reform

- History of cyberbanking

- History of coins

- History of the rupee

- History of the U.s.a. dollar

- Manillas

- Merchandise beads

References [edit]

- ^ "What is Coin?".

- ^ a b c d Denise Schmandt-Besserat, Tokens: their Significance for the Origin of Counting and Writing

- ^ Keynes, J.1000. (1930). A Treatise on Money. Volume I, p. xiii

- ^ a b Kramer, History Begins at Sumer, pp. 52–55.

- ^ a b Charles F. Horne (1915). "The Code of Hammurabi : Introduction". Yale Academy. Archived from the original on viii September 2007. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- ^ *Graham Flegg, Numbers: their history and meaning, Courier Dover Publications, 2002 ISBN 978-0-486-42165-0, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Beckmann, Petr (1971). A History of π (PI). Boulder, Colorado: The Golem Press. p. 8. ISBN978-0-911762-12-9.

- ^ Friedlob, G. Thomas & Plewa, Franklin James, Understanding balance sheets, John Wiley & Sons, NYC, 1996, ISBN 0-471-13075-three, p. 1

- ^ a b c Graeber, David (12 July 2011). Debt: The First v,000 Years . ISBN978-i-933633-86-2.

- ^ a b Graeber, David (26 August 2011). "What is Debt? – An Interview with Economic Anthropologist David Graeber".

- ^ Robert A. Mundell, The Birth of Coinage, Discussion Paper #:0102-08, Section of Economics, Columbia University, February 2002.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 April 2014. Retrieved 21 Baronial 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived re-create as title (link) - ^ a b M M Postan, East Miller (1896). The Cambridge Economic History of Europe: Trade and industry in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press, 28 August 1987. ISBN0521087090.

- ^ William Arthur Shaw (1987). The History of Currency, 1252–1896. Library of Alexandria, 1967. ISBN1465518878 . Retrieved four June 2012.

- ^ "Sir Isaac Newton's state of the gold and silvery coin (25 September 1717)". Pierre Marteau.

- ^ "Mineral Profiles" (PDF). U.Due south. Geological Survey.

- ^ a b Moseley, F (2004). Marx's Theory of Money: Modern Appraisals . New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 65. ISBN9781403936417.

- ^ von Mises, Ludwig (2013). The Theory of Money and Credit. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. p. 472. ISBN9781620871614.

- ^ Swedberg, Richard (2007). Joseph A. Schumpeter: His Life and Work. Malden, MA: Polity Press. p. 1902. ISBN9780745668703.

- ^ Tymoigne, Éric & Wray, L. Randall (2005), Coin: An Alternative Story, p. ii

- ^ Wray, L. Randall (2012), Introduction to an Alternative History of Money, p. 3

- ^ a b Coeckelbergh, Mark (2015). Money Machines: Electronic Financial Technologies, Distancing, and Responsibleness in Global Finance. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 98. ISBN9781472445087.

- ^ M0 (monetary base). Moneyterms.co.uk.

- ^ "M0". Investopedia. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved xx July 2008.

- ^ "M2". Investopedia. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- ^ "M2 Definition". InvestorWords.com. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- ^ "Discontinuance of M3", Federal Reserve, ten November 2005, revised nine March 2006.

- ^ Aziz, John (10 March 2013). "Is Inflation Always And Everywhere a Monetary Phenomenon?". Azizonomics . Retrieved 2 Apr 2013.

- ^ Thayer, Gary (16 January 2013). "Investors should presume that inflation volition exceed the Fed's target". Macro Strategy. Wells Fargo Advisors. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved two Apr 2013.

- ^ Carlson, John B.; Benjamin D. Nifty (1996). "MZM: A monetary aggregate for the 1990s?" (PDF). Economic Review. Federal Reserve Banking concern of Cleveland. 32 (2): 15–23. Archived from the original (PDF) on iv September 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ a b Humphrey, Caroline. 1985. "Barter and Economic Disintegration". Man, New Serial 20 (i): 48–72.

- ^ Mauss, Marcel. The Souvenir: The Grade and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies. pp. 36–37.

- ^ "What is Debt? – An Interview with Economic Anthropologist David Graeber". Naked Capitalism. 26 August 2011.

- ^ David Graeber: Debt: The First 5000 Years, Melville 2011. Cf. review

- ^ David Graeber (2001). Toward an anthropological theory of value: the false coin of our own dreams. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 153–154. ISBN978-0-312-24045-v . Retrieved ten Feb 2011.

- ^ S Meikle "Aristotle on Money" Phronesis Vol. 39, No. 1 (1994), pp. 26–44 Retrieved 2012-06-05

- ^ Aristotle Politics Translated by Benjamin Jowett MIT University

- ^ N. K. Lewis (2001). Gilded: The Once and Futurity Money. John Wiley & Sons, iv May 2007. ISBN0470047666 . Retrieved iv June 2012.

- ^ D Kinley (2001). Money: A Study of the Theory of the Medium of Exchange. Simon Publications LLC, one September 2003. ISBN193251211X . Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ kanopiadmin (29 September 2003). "The Origin of Money and Its Value". Mises Institute . Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ Strauss, Ilana E. (26 February 2016). "The Myth of the Barter Economy". The Atlantic . Retrieved 17 Feb 2020.

- ^ Innes, A. Mitchell 1913. "What is Money?". The Banking Police force Periodical (May): 377–408. Reprinted in L. Randall Wray (Ed.) 2004 "Credit and Land Theories of Money"

- ^ kanopiadmin (thirty August 2011). "Have Anthropologists Overturned Menger?". Mises Institute . Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ "The Myth of the Myth of Castling". Cato Institute. 15 March 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ "The Myth of the Myth of the Myth of Castling and the Return of the Armchair Ethnologists". Bella Caledonia. 8 June 2016. Retrieved 12 Feb 2020.

- ^ Cheal, David J (1988). "i". The Gift Economy. New York: Routledge. pp. i–nineteen. ISBN0-415-00641-4 . Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ Hill, Mark Andrew (2012). The Benefit of the Gift: Social Organisation and Expanding Networks of Interaction in the Western Swell Lakes Archaic. Ann Arbor: International Monographs in Prehistory. p. 4. ISBN9781879621442.

- ^ a b "What is Debt? – An Interview with Economic Anthropologist David Graeber". Naked Capitalism. 26 August 2011.

- ^ Gifford Pinchot – The Gift Economy Archived 18 July 2009 at the Wayback Motorcar. Context.org (2000-06-29). Retrieved on 2011-02-10.

- ^ Graeber, David (12 July 2011). Debt: The Commencement five,000 Years . ISBN978-i-933633-86-ii. Chapter 6

- ^ Roy Davies & Glyn Davies (iii June 2012). A Comparative Chronology of Money.

- ^ Tymoigne, Éric & Wray, 50. Randall (2005), Money: An Alternative Story

- ^ Aristotle. Politics I.9.

- ^ Michael Hudson, Cornelia Wunsch (Eds.) 2004, Creating Economic Gild: Record-keeping, Standardization, and the Development of Bookkeeping in the Ancient Near Due east

- ^ O'Sullivan, Arthur; Steven Yard. Sheffrin (2003). Economic science: Principles in activity. Upper Saddle River, New Bailiwick of jersey 07458: Prentice Hall. p. 246. ISBN0-13-063085-three.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: location (link) [ expressionless link ] - ^ Cripps, Eric Fifty., "The Structure of Prices in the Neo-Sumerian Economic system (I): Barley:Argent Price Ratios", 2007

- ^ Sheila C. Dow (2005), "Axioms and Babylonian idea: a reply", Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 27 (3), pp. 385–391.

- ^ The Reforms of Urukagina Archived 9 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. History-world.org. Retrieved on 2011-02-ten.

- ^ I I Rubin, A History of Economic Thought, translated Donald Filtzer, Ink Links, 1979 (original Moscow, 1929)

- ^ Genesis 17:13

- ^ secondary – Jean Andreau (Director of Studies at the École pratique des hautes études, Paris) (14 October 1999). Banking and Business concern in the Roman World. Cambridge University Press, 14 October 1999. ISBN9780521389327 . Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ secondary – Encyclopædia Britannica & French Lexicon (HarperCollins Publishers Limited 6 July 2010), Retrieved 2012-06-04

- ^ F W Madden, F W Fairholt – History of Jewish coinage, and of money in the Old and New Testament B. Quaritch, 1864 Retrieved 2012-05-04

- ^ J Free, H F Vos Archaeology and Bible History Zondervan, 15 September 1992, ISBN 0310479614 – Retrieved 2012-06-04

- ^ F Northward Magill, C J Moose Lexicon of World Biography: The Ancient World Taylor & Francis, 23 January 2003 ISBN 1579580408 Retrieved 2012-06-04

- ^ I M Wise – History of the Israelitish nation: from Abraham to the present fourth dimension J. Munsell, 1854 Retrieved 2012-06-04

- ^ David Graeber: Debt: The First 5000 Years, Melville 2011. Cf. http://www.socialtextjournal.org/reviews/2011/x/review-of-david-graebers-debt.php Archived ten December 2011 at the Wayback Motorcar

- ^ Schaps, David M. "The Invention of Coinage in Lydia, in India, and in China" (PDF). XIV International Economic History Congress, Helsinki 2006. Session thirty. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- ^ Total text of "The primeval coins of Greece proper". archive.org. Retrieved on 2011-02-ten.

- ^ a b L Adkins, R A Adkins (1998). Handbook to Life in Aboriginal Rome. Oxford University Printing, 16 July 1998. ISBN0195123328 . Retrieved ix June 2012.

- ^ Coin images

- ^ Ancient coinage of Aegina. snible.org. Retrieved on 2011-02-10.

- ^ Giuseppe Amisano, "Cronologia e politica monetaria alla luce dei segni di valore delle monete etrusche e romane", in: Panorama numismatico, 49 (genn. 1992), pp. 15-twenty

- ^ Goldsborough, Reid. "World's First Coin"

- ^ D Harper – etymology online Retrieved 2012-06-09

- ^ P Bayle, P Desmaizeaux, A Tricaud, A Gaudin – The dictionary historical and critical of Mr. Peter Bayle, Book 3 Printed for J. J. and P. Knapton; D. Midwinter; J. Brotherton; A. Bettesworth and C. Hitch ... [and 25 others], 1736 – Retrieved 2012-06-09

- ^ P B Harvey, C Eastward Schultz Organized religion in Republican Italian republic Cambridge University Press, 2006 – ISBN 052186366X Retrieved 2012-06-09

- ^ Rome Reborn – University of Virginia – Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities Retrieved 2012-06-09

- ^ a b Sargent, Thomas; Velde, Francois (2001). The Princeton Economic History of the Western World: The Large Problem of Small Alter. Princeton University Printing. p. 45.

- ^ Daniel R. Headrick (1 Apr 2009). Technology: A World History . Oxford University Press. pp. 85–. ISBN978-0-19-988759-0.

- ^ Patricia Buckley Ebrey, and Anne Walthall, East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. (2006) p. 156.

- ^ Bowman (2000), 105.

- ^ Gernet (1962), 80.

- ^ Ebrey et al., 156.

- ^ Gernet, fourscore.

- ^ a b "Mughal Coinage". Archived from the original on 5 October 2002.

Sher Shah issued a money of silvery which was termed the Rupiya. This weighed 178 grains and was the precursor of the mod rupee. It remained largely unchanged till the early on 20th Century

- ^ a b Subodh Kapoor (Jan 2002). The Indian encyclopaedia: biographical, historical, religious ..., Volume 6. Cosmo Publications. p. 1599. ISBN81-7755-257-0.

- ^ a b Turner, Sir Ralph Lilley (1985) [London: Oxford University Press, 1962–1966.]. "A Comparative Dictionary of the Indo-Aryan Languages". Includes iii supplements, published 1969–1985. Digital Southward Asia Library, a project of the Center for Research Libraries and the University of Chicago. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

rū'pya 10805 rū'pya 'beautiful, begetting a stamp' ; 'silver'

- ^ Turner, Sir Ralph Lilley (1985) [London: Oxford University Press, 1962–1966.]. "A Comparative Dictionary of the Indo-Aryan Languages". Includes iii supplements, published 1969–1985 . Retrieved 26 August 2010.

rūpa 10803 'form, dazzler'

- ^ a b Shoaib Daniyal. "History revisited: How Tughlaq's currency modify led to anarchy in 14th century Republic of india". scroll.in. Retrieved fourteen February 2017.

- ^ Theodore Roosevelt; Kermit Roosevelt (1929). "Trailing the giant panda". Nature. Scribner. 124 (3138): 944. Bibcode:1929Natur.124R.944.. doi:x.1038/124944b0. S2CID 4086078.

... The currency in general use was what was known at the Tibetan rupee ...

- ^ Moshenskyi, Sergii (2008). History of the weksel: Bill of exchange and promissory note. p. 55. ISBN978-1-4363-0694-ii.

- ^ Marco Polo (1818). The Travels of Marco Polo, a Venetian, in the Thirteenth Century: Beingness a Description, past that Early on Traveller, of Remarkable Places and Things, in the Eastern Parts of the World. pp. 353–355. Retrieved xix September 2012.

- ^ The Alchemists: Three Primal Bankers and a World on Burn – Neil Irwin – Google Books

- ^ De Geschiedenis van het Geld (the History of Money), 1992, Teleac, page 96

- ^ Davies, Glyn, ''A History of Money'', University of Wales, 1994, pp. 172, 339. ISBN 0-7083-1717-0

- ^ Banaji, Jairus (2007). "Islam, the Mediterranean and the Rise of Capitalism". Historical Materialism. xv (i): 47–74. doi:10.1163/156920607X171591. ISSN 1465-4466. OCLC 440360743. Archived from the original on 23 May 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ Lopez, Robert Sabatino; Raymond, Irving Woodworth; Lawman, Olivia Remie (2001) [1955]. Medieval merchandise in the Mediterranean world: Illustrative documents. Records of Western culture.; Records of civilization, sources and studies, no. 52. New York: Columbia University Printing. ISBN978-0-231-12357-0. OCLC 466877309. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012.

- ^ a b Labib, Subhi Y. (March 1969). "Capitalism in Medieval Islam". The Periodical of Economical History. 29 (1): 79–86. doi:10.1017/S0022050700097837. ISSN 0022-0507. JSTOR 2115499. OCLC 478662641.

- ^ Turner, Sir Ralph Lilley (1985) [London: Oxford University Printing, 1962–1966.]. "A Comparative Lexicon of the Indo-Aryan Languages". Includes three supplements, published 1969–1985. Digital Southern asia Library, a project of the Center for Research Libraries and the Academy of Chicago. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

rūpa 10803 'grade, beauty'

- ^ Davies, Glyn, ''A History of Money'', University of Wales(England), 1994, pp. 146–151 ISBN 0-7083-1717-0

- ^ Richards

- ^ Thus by the 19th century "[i]n ordinary cases of deposits of money with cyberbanking corporations, or bankers, the transaction amounts to a mere loan or mutuum, and the banking concern is to restore, not the same money, but an equivalent sum, whenever information technology is demanded". Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Law of Bailments (1832, p. 66) and "Money, when paid into a bank, ceases altogether to be the coin of the chief (meet Parker v. Marchant, 1 Phillips 360); it is then the coin of the banker, who is bound to return an equivalent by paying a similar sum to that deposited with him when he is asked for information technology." Lord Chancellor Cottenham, Foley v Hill (1848) 2 HLC 28.

- ^ Richards. The usual denomination was 50 or 100 pounds, so these notes were not an everyday currency for the common people.

- ^ Richards, p. 40

- ^ Geisst, Charles R. (2005). Encyclopedia of American business history. New York. p. 39. ISBN978-0-8160-4350-7.

- ^ Karl Gunnar Persson, An Economic History of Europe: Noesis, Institutions and Growth, 600 to the Present Cambridge University Printing, 28 January 2010, ISBN 052154940X – Retrieved 2012-06-03

- ^ "History of Indian Currency". The Economic Times.

- ^ Stearns, David 50. (2011). Electronic Value Exchange: Origins of the Visa Electronic Payment System. London: Springer. p. 1. ISBN978-one-84996-138-7. Available through SpringerLink.

- ^ The Effect of Consumer Interest Rate Deregulation on Credit Carte du jour Volumes, Charge-Offs, and the Personal Bankruptcy Rate Archived 2008-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, Federal Eolith Insurance Corporation "Bank Trends" Newsletter, March, 1998.

- ^ "Credit cards: how exercise they work, advantages and downsides". banqo.fr . Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 July 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived re-create as title (link) - ^ Eveleth, Rose (24 July 2015). "The truth nearly the death of greenbacks". BBC. Retrieved four Dec 2018.

- ^ "Understanding Digital Money - Advantages of Digital money| Motilal Oswal".

- ^ Southward., L. (2 November 2015). "Who is Satoshi Nakamoto?". The Economist explains . Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ^ .Nakamoto, Satoshi (2008). "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Greenbacks System" (PDF).

- ^ Chaum, David (1982). "Blind signatures for untraceable payments" (PDF). Section of Computer Science, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA.

Further reading [edit]

- Alvarado, Ruben, Follow the Coin: The Money Trail Through History, Wordbridge 2013.

- Bowman, John S. Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Civilization. (Columbia Up, 2000). ISBN 0231110049

- Dean, Austin. Prc and the End of Global Silver, 1873–1937 (Cornell UP, 2020).

- Del Mar, Alexander. (1885). A History of Money in Ancient Countries from the Primeval Times to the Present. London: George Bell & Sons. ISBN 0-7661-9024-two

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley, and Anne Walthall. East asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006) ISBN 0618133844

- Eichengreen, Barry, and Peter Temin. The gold standard and the great low (National Bureau of Economic Inquiry, 1997) online.

- Eichengreen, Barry J., and Marc Flandreau, eds. The gold standard in theory and history (Psychology Press, 1997).

- Gernet, Jacques (1962). Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250–1276. Stanford: Stanford Academy Press. ISBN 0-8047-0720-0

- Jacob Goldstein (2020). Money: The Truthful Story of a Made-Up Thing. Hachette Book. ISBN978-0316417198.

- Irigoin, Alejandra. "The finish of a silverish era: the consequences of the breakdown of the Spanish Peso standard in China and the United States, 1780s-1850s." Journal of Globe History (2009): 207-243. online

- Jevons, W. S. Money and the Mechanism of Exchange. (London: Macmillan, 1875), .

- Menger, Carl, "On the Origin of Coin"

- Richards, R. D. Early history of cyberbanking in England. London: R. S. Rex (1929).

- Sehgal, Kabir (2015). Coined: The Rich Life of Money and How Its History Has Shaped United states . Yard Central Publishing. ISBN978-1455578528.

- Weatherford, Jack. The History of Coin. (New York: Crown Publishers, 1997).

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Money. |

- The Marteau Early 18th-Century Currency Converter A Platform of Research in Economic History.

- Historical Currency Conversion Page past Harold Marcuse. Focuses on converting German marks to United states of america dollars since 1871 and inflating them to values today, only has much boosted information on the history of currency exchange.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_money

Posted by: pickettofeautioull.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Did The Development Of Coined Money Change Trade?"

Post a Comment